GREEN BAY, Wis. — The three women sitting around a table at a busy lunch spot share a grim camaraderie. It’s been more than a year since an 1849 law came back into force to criminalize abortion in Wisconsin. Now these two OB-GYNs and a certified midwife find their medical training, skill, and acumen constrained by state politics.

“We didn’t even know germs caused disease back then,” said Dr. Kristin Lyerly, an obstetrician-gynecologist who lives in Green Bay.

Like undertakers and garbage haulers, obstetricians see the nitty-gritty of human existence that can be ghastly and grotesque. A fetus with organs growing outside its body. A woman forced to birth a baby with no skull to push open her cervix.

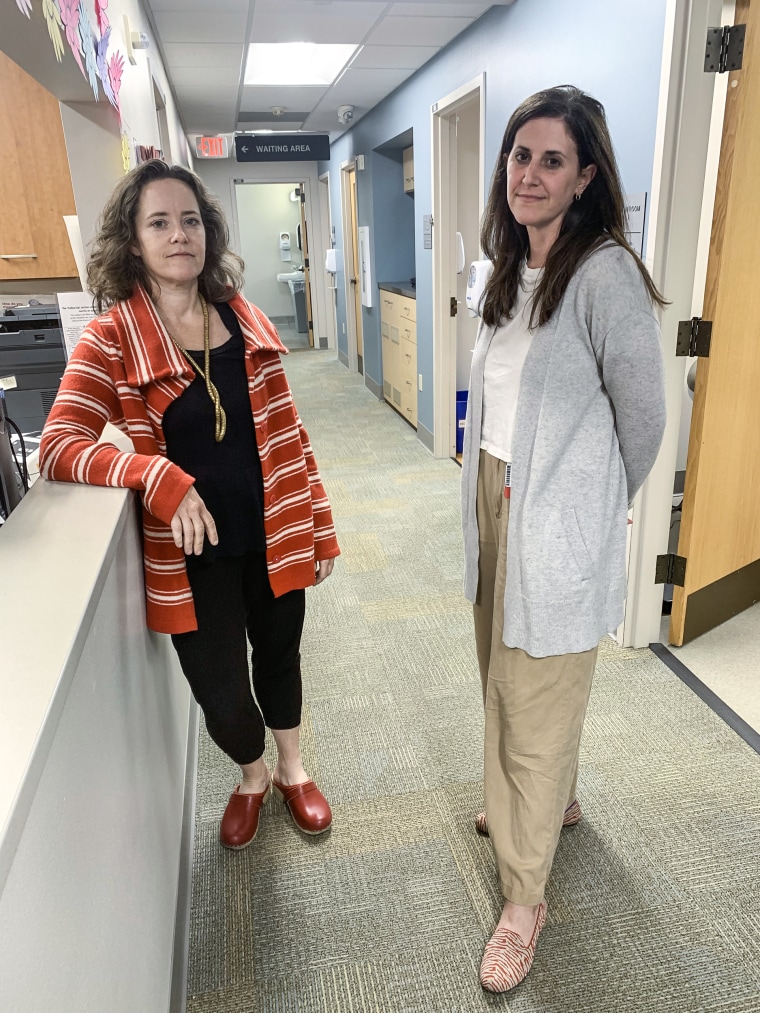

OB-GYN Dr. Anna Igler regularly performed abortions for medically indicated reasons before the Supreme Court overturned the right to abortion last year. She is beyond fed up.

“I’m at a different level with it now,” she said. “Part of me is so upset at people for sticking their head in the sand.” With her world inside a Green Bay hospital in turmoil, she said, she cannot fathom that people might be oblivious to the government’s incursion into their medical care.

“So many people I’ve talked to have no idea what our laws are in our state,” she said.

Even now, a year later, Igler said, expectant parents come into her office with the assumption that if their fetus has a lethal genetic disorder, like anencephaly or trisomy 13 or 18, they can end the pregnancy safely.

“They are shocked when I tell them they can’t,” Igler said, “and they are shocked when I tell them we are following the law from 1849.”

She’s referring to the state’s original abortion law, which was passed before the Civil War, when women could not vote or own property. The law makes it a felony to perform an abortion at any stage of pregnancy, unless it would prevent the death of the pregnant person.

It had been some time since these women were together, and they were eager to compare notes. The certified midwife spoke on the condition of anonymity because she’s not authorized to talk to the media and is concerned about losing her job at a local health system. “My biggest issue right now is getting medication to end a pregnancy that has already passed,” she said. “I’m finding locally that pharmacists just won’t dispense the medication.”

She offered a rundown: One pharmacist told her patient the medication, misoprostol, which causes cramping to expel the pregnancy tissue, had expired. Another, at a Walgreens, simply canceled the order. A third said he needed preauthorization, noting, “It’s a $3 pill, and we’re not going to get preauthorization on a weekend.”

The midwife said she and physician colleagues in her practice have half-joked that they’d send a gift basket to one pharmacist in town she’d found who will fill their prescriptions.

Now, when a patient miscarries, the midwife said, “we warn patients that this might happen, and they are like, ‘But my baby is dead,’ and I tell them, ‘I’m sorry. I don’t know why, but a lot of pharmacists in Green Bay think it’s their job to police this.’”

A year into this new era of compulsory birth for most women with pregnancies, the dismay and disorientation of those first few months have settled into, if not acceptance or resignation, a kind of chronic fear. Obstetricians and gynecologists are fearful of practicing medicine as they were trained.

A recent survey by pollsters at KFF of OB-GYNS in states with abortion bans found 40% felt constrained in treating patients for miscarriages or other pregnancy-related medical emergencies since the Supreme Court’s Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision last summer. Nearly half of them said their ability to practice standard medical care has become worse.

The specter of felony charges and losing a medical license has led to futile exercises.

Under the Wisconsin abortion ban — and bans in at least 13 other states — physicians who cannot detect fetal cardiac activity should, in theory, not face criminal charges for prescribing medication abortion pills or performing abortion procedures. But physicians here in Green Bay, and others interviewed in Madison, said they — and the litigation-averse hospitals they work for — are requiring patients whose pregnancies are no longer viable, or who have gestational sacs that do not contain an embryo, to return for multiple ultrasounds, forcing them to carry nonviable pregnancies for weeks.

Before Wisconsin’s abortion ban, Igler would typically use the ultrasound machine in her office to detect when a patient’s pregnancy had ceased. She would break the news to expectant parents there. In some cases, a patient wanted further ultrasounds and she would refer them to the fetal-imaging department. It might help with their grieving, and “I was happy to do that for them,” Igler said.

But her bedside ultrasound can’t record and save the images that Igler would now need to prove that her medical judgment was reasonable during a criminal prosecution, so she is compelled to send all her patients for additional imaging.

“It seems cruel to show a woman her nonviable, dead baby and then say, ‘Well, now I have to bring you over to fetal imaging so we can record a picture and you have to see it again,’” she said.